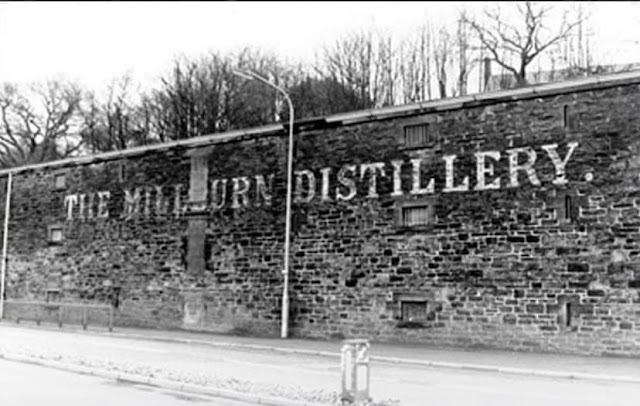

The House of Sanderson Millburn Distillery 1963

My thanks to Bill for reaching out and giving me a virtual nudge regarding Millburn, as well as for bringing to my attention an entry in this book he found by Ross Wilson from 1963.

The House of Sanderson is one of those publications created by blenders, companies, distilleries, and others to help solidify their legacy. It provides a distinctive perspective on a firm, specifically the Sanderson family business and VAT 69 brand, by tracing the origins of their journey. Typically, these types of publications were produced in limited quantities and were often intended for individuals and employees connected to a company. We have encountered contemporary counterparts like Ian Buxton's Glenfarclas 175 book, which provides insights into company archives and details.

The illustration above is created by William Paine, who contributed to depicting moments in the book through plates, illustrations, and portraits. While it's a lovely addition, it holds less importance in this modern context and reflects the romantic Highland imagery presented in the text.

The benefit of such publications lies in the access to information from those at the very core of a company, distillery, or brand. Often, this information is preserved by families, with their legacy being passed down to the next generation, as seen with Gordon & MacPhail, for instance. Consequently, these books often contain insights and details that are not available elsewhere.

Through research, we frequently uncover moments that are difficult to articulate, such as acquisitions or significant decisions. Books like these can sometimes provide valuable explanations, thus becoming essential tools as well as holding financial value for collectors and enthusiasts.

As is customary, all rights remain with the original author if they are still relevant, and I have carefully transcribed this information while preserving the American spelling. In the UK, publishing typically anticipates a period of 70 years from the author's death, or 70 years from publication if the work lacks attribution. Like many aspects of life, the passage of time can create confusion, yet these research initiatives are consistently non-profit, fully accredited and I respect the original work.

Now, we can delve into what this summary contributes concerning Millburn; this opening paragraph undoubtedly offers substantial context for the establishment of a new company. Like many aspects of life, I enjoy stepping back from the details to reflect on the context, a perspective that Ross articulately presents by highlighting the overarching themes and rationale of the industry at this time.

'Someone else did, however, gain an interest. the rationalization of the twenties finally caught up with that old Leith firm. The probability of Repeal, their attention to Scotch Whisky production and distribution, and reputation of Sanderson's as one of the leading independent non-combine Whisky firms in Scotland, led Booth's Distilleries Limited to approach Wm. Sanderson & Son Limited on the subject of amalgamation. And that year - which had witnessed the final retirement of Mark Sanderson, who seemed all set to gain his century, and which saw his replacement by another of the family, Martin - closed with the voluntary liquidation of the firm founded by William Sanderson. That liquidation was only a legal and commercial formality; the firm passed over to Booth's Distilleries, the new partners being Mr O. Bertram and Kenneth W.B. Sanderson. Early in 1935, again as a formal procedure, the firm was incorporated with O. Bertram as chairman, Kenneth as director and R.C. Marshall as secretary.

The world was emerging from the slough of depression, Prohibition had been repealed in the United States, VAT 69 was sweeping the American market, and in 1936 H.R.H. the Prince of Wales set another seal of royalty on VAT 69 by granting to the firm a Warrant of Appointment. More, memories of the two Shackleton expeditions to the South Pole were revived by VAT 69 being taken on the British Grahamland Antarctic Expedition.'

What is it that draws Inverness distilleries to far flung expeditions? The most renowned among them is Glen Mhor, which gained fame for its involvement in the Shackleton expedition many decades prior. In contrast, the Grahamland expedition took place from 1934 to 1937 and was a scientific triumph, yet it also signified the closing chapter of such private, almost celebrity-style adventures into the remote corners of the Earth.

Crucially, this entry provides insight into the historic Sanderson firm and its transition to Booth's Distilleries as a successor. While a specific date isn't mentioned, our previous research indicates that this occurred in the early 1920s, specifically in 1921, a notably challenging time for scotch whisky as a whole. The Pattison crisis of 1898 marked the end of a prosperous era and severely undermined consumer confidence. Numerous distilleries and blenders failed to bounce back, and the signs of recovery took longer than expected to emerge. Additionally, the impact of the First World War was felt, and by 1920, the impending threat of Prohibition loomed, which would severely impact a key market for whisky producers.

These were incredibly challenging times, and consumer preferences were shifting as well. Mergers and acquisitions became the norm as majority stakes in distilling and blending led to the emergence of larger, more powerful companies, some of which still exist today.

'When Booth's amalgamated with Sanderson's, they bought more than just the name and reputation of the firm into the new group. They then owned three outstanding distilleries in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, distilleries of more than passing interest. They were the Stromness distillery in the Orkneys, overlooking the meeting of the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea; the Royal Brackla distillery, near the ancient and royal Burgh of Nairn, the property of Bisset's, of whom William had earlier been sole partner; and Millburn distillery, near Inverness.'

This newly established company boasted three distinct distilleries in its portfolio. Stromness was on the brink of closure, and I consider myself lucky to have experienced its whisky a couple of times, and it confirmed a quality whisky, connected to its unique setting. Yet, it was a small operation, short on investment and likely very inefficient by the standards of the period, and situated far from the main hubs. In the ever-evolving landscape of scotch whisky, it symbolised a past era, and a legacy challenge.

The theme of unusual partnerships is evident as Royal Brackla stands out as another strange bedfellow, still in operation today, bolstered by its royal endorsement. Throughout its history, this distillery has frequently found it challenging to carve out a unique identity beyond nobility, primarily serving blenders, which continues to be its main focus in contemporary times. Then, the last of the unlikely trio is our main focus, Millburn.

'Each deserves a moment's attention; each illustrates some aspect of the ancient craft of making Scotch Whisky, and each played its part in giving that spirit its present dominance on the palates of the civilised world. Stromness distillery lay - it has since been discontinued - in a sheltered bay on the west side of Orkney, and in the sailing days America-bound ships, particularly from Leith, found Stromness a convenient port of call, above all in the French wars of the eighteenth century: Stromness was then a rendezvous for trading vessels awaiting escorts across the Atlantic. Later it was regularly visited by Hudson's Bay Company ships, and every year a hundred or so men of Stromness used to leave their town to carry on the fur trade in the North and West of Canada, the most famous being Dr John Rae, the discoverer of the unfortunate Franklin expedition, and a well-known Arctic explorer. They all took away with them some of the spirit of Stromness, some of the unblended Whisky made at the little distillery there. That plant was founded about 1784. Certainly after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Hector Munro, back from death, set about making uisage beatha, the water of life. After his death it passed from one to another; non, in line with any unwritten law of distilling changing the shape of the stills which were very small by any standards, and led William Sanderson to blend and bottle a special brand of his own, 'The Small Still'. One of the stills was indeed, only eighty-three gallons in capacity.

The Royal Brackla distillery, close to Nairn, was the first Scotch Whisky distillery to be given the prefix 'royal' by William IV, about the time of the death of Captain Mark Sanderson. Moreover, it lies in the heart of the country made famous by Shakespeare's 'Macbeth'.

The water of the plant is drawn from the Cawdor Burn and nearby is Cawdor Castle, the home of Macbeth who became King of Scotland. The present distillery was first built there by Captain William Fraser about 1812. but immediately ran into trouble over the distilling laws when it was a race between the distiller and the excise officer, a position only sorted out with Peel. Huskisson rationalized the law on the subject in 1823. Since then the distillery's progress has never been stopped, although ownership has occasionally been changed. At one time it was in the hands of Bisset & Company; it then passed into Booth's ownership, then into the group they formed with Wm. Sanderson & Son, and eventually into the hands of Scottish Malt Distillers Limited, a group whose beginnings we noted after the Lloyd George budget of 1909-1910.'

Since Millburn is part of a trio, I thought it worthwhile to include information about the other distilleries, as it might be beneficial for others. Royal Brackla and Stromness each have distinct histories, yet only one remains today. Aside from a new parent company, each distillery (including Millburn) can trace their roots back to the origins of the whisky industry, and they are not merely recent constructs during a period of growth.

'Millburn distillery, near to Inverness, the capital of the Highlands, is likewise steeped in history of the land about it. It was formalized about 1805, but still carries the tale of the illicit woman distiller of the site, who found in the act, exclaimed to the officer: "Oh, sir, I am nearly fainting... give me just one mouthful out of the jar." It was granted; she dashed it into his eyes, and was away, to distil another day! Another tale of the distillery is how in the days of illicit distilling the Revenue officers carried off a cask to the inn; it was located precisely by the smuggler, wo bored a whole through the floor into the cask, drained it, and was away with the Whisky. The distillery not only abounds in these tales, but in the best Highland Malt Whisky, of course. It was built part in the Burgh of Inverness, part in the county of the same name, the Millburn being the line of demarcation. But it has been extended many times since that first building, though at the time of which we speak it drew its water from the same source, a moor on the east side of which was fought the battle of Culloden, where Bonnie Prince Charlie's troops were butchered by the Duke of Cumberland.'

Ultimately, it all boils down to this one paragraph for any insights regarding Millburn. This research involves examining every possible detail, often with little success. However, even the smallest piece of information can prove to be valuable.

Numerous stories are linked to the distilleries of Inverness, with Glen Albyn's connection to a nearby inn being the most vibrant, and I believe it to be true. There is always a kernel of truth in such narratives. Perhaps the key takeaway isn't about the woman or the officer's trusting demeanour, but rather that the parish of Millburn, located just outside Inverness, provided an ideal site for illicit distilling. And history shows us that these sites often became the best locations for fully legalised distilling.

Booth's and their predecessors heavily promoted Millburn's quality in their advertisements, such as the 'finest Highland Malt Whisky' slogan featured in ads from 1898 and 1900. This was a common practice throughout the industry, which still persists today with claims of using the finest barley, the best wood, and so on.

Fortunately, the water source remained uncontaminated by past events or the nearby presence of an army base situated high above the site. Even now, the burn flows, albeit beneath the busy road leading into the city. The topic of water will certainly arise in discussions about Millburn and some future considerations.

In summary, this historical book gives us good insight into the formation of a new company and its motivations. The fact that the research did not take us more into the distillery itself and satisfy our thirst for production details, the men and tools involved, should not come as a major surprise.

Minimal documentation exists from that era, as evidenced by the Diageo archives, which would eventually take ownership of the distillery through its predecessor, D.C.L., in 1937. There remains a challenging Millburn puzzle to piece together, yet we will persist in our efforts, and the whisky will always prevail.

Comments

Post a Comment